Vietnam’s industrial sector is a backbone of its booming economy – and it faces growing threats from natural disasters. In recent years, Vietnam and its neighbors have experienced a series of extreme events, from powerful storms and floods to tremors from distant earthquakes, underscoring the urgent need for resilient infrastructure. This article explores how Vietnam’s industrial sector is building resilience against earthquakes and other natural disasters, highlighting recent developments, the role of the Building Resilience Index (BRI), current strategies and technologies, and key partnerships bolstering disaster risk reduction.

Vietnam’s Exposure to Disasters: Recent Developments and Risks

Vietnam is highly vulnerable to natural hazards, ranking among the top in Asia for disaster risk. Over 1,100 natural disasters struck Vietnam in 2023 alone, causing significant loss of life. The country’s geography – a long coastline and river basins densely packed with people and industry – exposes it to typhoons, floods, droughts, and sea-level rise. In fact, Vietnam has been one of the world’s most climate-affected areas in the past two decades. Climate change is intensifying these events: heavy rainfall triggers landslides and floods that can shut down highways and even airports, while rising temperatures fuel more extreme typhoons and heatwaves.

One striking example was Typhoon Yagi (2024), which caused severe disruptions in northern Vietnam’s supply chains. A survey of 216 companies found that 82.4% of businesses experienced moderate to severe impacts from Yagi – including power outages, flooded roads, and damaged inventory. Logistics providers and port operators were hardest hit, highlighting how a single storm can ripple through industrial operations. While most firms managed to recover within two weeks through rapid resource mobilization, the event underscored the need for stronger preventive measures and backup systems. Earlier storms have been even more devastating: for instance, Typhoon Damrey in 2017 caused about $1 billion in losses in Vietnam. In 2020, prolonged flooding in central Vietnam disrupted thousands of businesses – many factories had to halt production due to worker shortages, supply delays, or facility damage. These examples illustrate that extreme weather is not a distant threat but a present danger to Vietnam’s industrial and economic stability.

Even earthquake risk, while lower than in some neighboring countries, cannot be ignored. Vietnam lies near several seismic zones and occasionally feels quakes from across the region. A vivid reminder came on March 28, 2025, when a magnitude 7.7 earthquake struck central Myanmar. The tremor – one of the strongest in Southeast Asia in recent years – was powerful enough to sway high-rise buildings from Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City. Office workers in HCMC evacuated as they felt buildings shake, and residents of Hanoi’s tall apartments saw furniture and even water in fish tanks slosh from the distant quake. Fortunately, Vietnam suffered no casualties or serious damage from that event. However, the incident was a wake-up call: it highlighted that major regional quakes can affect Vietnam’s urban centers, and that industrial facilities (especially factories with heavy equipment or hazardous materials) must be prepared for seismic vibrations. Vietnam’s own seismic history is mild – the country has not recorded a deadly earthquake in the past century – but scientists warn of possible moderate quakes along local fault lines. Thus, even as floods and storms remain the dominant concern, earthquake resilience must be part of the industrial risk management toolkit.

The Need for Resilience in Industry

The confluence of these hazards means Vietnam’s industrial hubs face multi-faceted risks. Many manufacturing zones are located in low-lying coastal areas or river deltas (e.g. the Mekong Delta and Red River Delta regions) that are prone to typhoon damage and flooding. Climate projections indicate that by 2030, major cities like Ho Chi Minh City could see more intense heatwaves (which can reduce worker productivity and strain power supply) and Hanoi could see heavier downpours (overwhelming drainage systems and increasing flood risk). Industrial parks in coastal provinces also contend with storm surge and coastal erosion, which could worsen as sea levels rise.

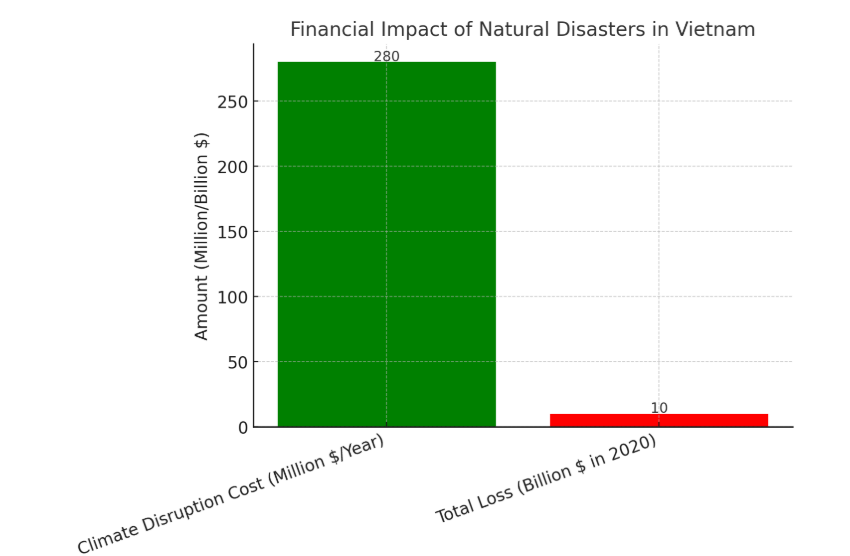

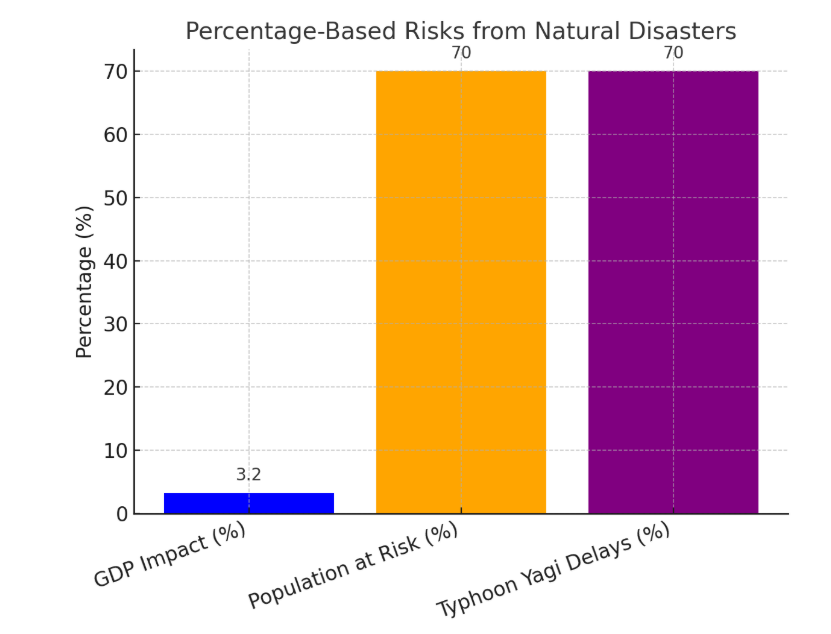

All these factors threaten the continuity of operations, safety of workers, and integrity of assets in the industrial sector. The economic stakes are enormous. Climate-related infrastructure disruptions already cost businesses in Vietnam an estimated $280 million each year on average. Overall, Vietnam lost around $10 billion in 2020 (equivalent to 3.2% of GDP) due to climate and disaster impacts. More than 70% of the population is at risk from natural hazards – particularly vulnerable are poorer communities who often provide labor for industry.

Picture 1: Financial Impacr of Natural Disasters in VietNam

For the industrial sector, this means not only direct damage to factories and warehouses, but also supply chain breakdowns, workforce displacement, and power or transport outages that halt production. For example, after Typhoon Yagi, nearly 70% of companies surveyed reported delays in shipments or production. Such interruptions can cascade globally, given Vietnam’s key role in electronics, apparel, and other supply chains.

Picture 2: Perventage-Based Risks from Natural Disasters

Building resilience is therefore not just a safety issue, but an economic imperative to protect Vietnam’s growth and investment climate. Encouragingly, awareness of these risks is translating into action. The government and private sector are increasingly focused on “risk-proofing” industrial development. This includes updating building codes, investing in protective infrastructure, adopting new technologies for disaster monitoring, and ensuring business continuity plans are in place. International indices and frameworks are also being introduced to guide and benchmark resilience. One pioneering tool making headway in Vietnam’s construction and industrial scene is the Building Resilience Index (BRI).

Building Resilience Index (BRI): A New Tool for Safer Buildings

An IFC expert introduces the Building Resilience Index (BRI) at its Vietnam launch in Hanoi on April 20, 2023. The BRI is a web-based platform that helps assess a building’s resilience to hazards, aiming to make structures – including industrial facilities – safer against disasters. In April 2023, Vietnam became one of the first countries to pilot the Building Resilience Index (BRI) – an innovative resilience-rating system for buildings developed by the International Finance Corporation (IFC). BRI is essentially a web-based hazard mapping and resilience assessment framework that evaluates how well a given building or project can withstand climate and disaster risks.

By inputting a project’s location and design features, developers and engineers can use BRI to identify site-specific hazards (like flood plains, cyclone wind zones, or seismic fault proximity) and see whether the building’s design includes adequate protective measures. The tool then generates a resilience scorecard and allows builders to disclose these ratings – similar in spirit to how green building certifications (like IFC’s EDGE or LEED) work, but focused on disaster readiness. BRI’s introduction in Vietnam was supported by the Australian government and accompanied by the integration of Vietnam’s own hazard data into the platform. This means local hazard maps (flood inundation maps, typhoon wind intensity maps, earthquake ground acceleration maps, etc.) are built into the BRI system, providing more accurate risk assessments for Vietnamese contexts. Initially, three pilot projects in sectors such as residential, office, and hospitality are being assessed to fine-tune the index for Vietnam.

However, the industrial sector stands to benefit greatly from BRI as well. Industrial buildings – factories, warehouses, power plants – could be evaluated for resilience and retrofitted or built to higher standards based on the findings. For instance, an electronics factory in a coastal province might learn through BRI that its site faces high cyclone wind risk and thus decide to strengthen its roof and wall connections or elevate critical equipment above likely flood levels. Vietnamese officials see BRI as an important tool to mainstream resilient construction. Nguyen Cong Thinh, Deputy Director at the Ministry of Construction, emphasized that integrating climate-resilient measures into urban development (which includes industrial zones) is crucial to “avoid losses of residential and industrial assets” while still pursuing sustainable, net-zero growth.

In other words, BRI can help ensure that new factories or commercial buildings are designed not only for productivity but also for safety, so that an earthquake or storm doesn’t wipe out years of investment. Thomas Jacobs, IFC’s country manager, noted that with climate threats rising, buildings must be resilient to hazards like cyclones, flooding, fire, and landslides, especially in dense urban areas. Equipping developers and investors with BRI, he said, will strengthen Vietnam’s climate agenda and promote a “greener, more sustainable, and more inclusive economy.”

Although BRI is new, it follows the successful model of voluntary building standards – much like the green building movement. In fact, it’s expected to replicate the uptake of IFC’s Excellence in Design for Greater Efficiencies (EDGE) green building program. EDGE has already helped many projects in Vietnam save money and cut emissions; similarly, BRI could help projects save on potential disaster losses and reduce downtime. Over the next few years, as more Vietnamese developers use BRI, we may see “resilience ratings” becoming a norm in real estate and industrial development, guiding everything from factory design to the insurance premiums a facility might pay. Ultimately, widespread use of tools like BRI will raise the bar for construction quality – ensuring that buildings are not just modern and efficient, but also robust against the shocks and stresses that nature may bring.

Strategies and Policies for Industrial Resilience

Building resilience requires more than one-off projects – it demands strategic, systemic changes. Vietnam’s government has recognized this and implemented a comprehensive policy framework for disaster risk reduction and climate adaptation across sectors. Notably, the country enacted its first-ever Law on Natural Disaster Prevention and Control in 2014, which laid the groundwork for coordinated risk management nationwide. This was followed by a National Strategy for Disaster Prevention, Response and Mitigation to 2030 (with vision to 2050) approved in 2021. To operationalize the strategy, a National Plan for Disaster Prevention and Control (2021–2025) was released, focusing on concrete actions.

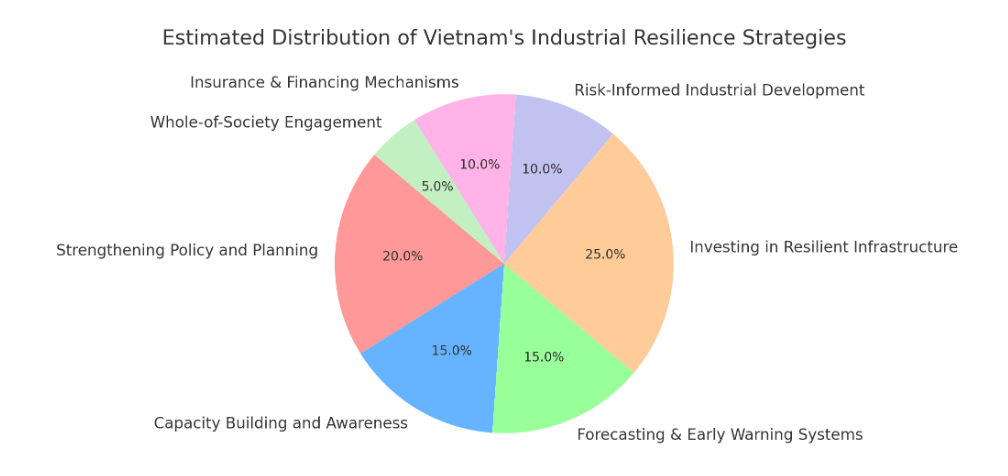

Picture 3: Estimated Distribution of Vietnam’s Industrial Resilience Strategies

The national strategy and plan set out specific targets and tasks to bolster resilience. Key priorities include:

- Strengthening Policy and Planning: Updating laws, regulations, and standards to embed disaster risk reduction into all aspects of development. This has involved updating building codes and technical standards – for example, Vietnam introduced a modern earthquake-resistant design standard in 2006 (based on Eurocode guidelines) and updated it in 2012, ensuring new industrial and civil buildings are structurally equipped to handle expected seismic forces. Land use planning is also being refined so that factories or warehouses are not built in the highest-risk zones without proper safeguards.

- Capacity Building and Awareness: Training local authorities, communities, and businesses in disaster preparedness. Many industrial parks now conduct regular emergency drills and have response plans for scenarios like chemical spills in floods or factory fires during earthquakes. The government has rolled out community-based disaster risk management programs in over 6,000 vulnerable communes, which indirectly benefits industry by protecting workers’ communities and local supply chains. Public awareness campaigns and school education ensure that the workforce is more knowledgeable about what to do when disaster strikes.

- Improving Forecasting and Early Warning Systems: A major focus has been upgrading the hydrometeorological and geophysical monitoring networks. Vietnam, with support from international partners, has invested in better weather radar, flood forecasting models, and even considering earthquake early warning in some areas. The goal is comprehensive risk information and early warnings that reach all stakeholders in time. For instance, the government is developing SMS alert systems and loudspeaker networks that can warn factories and communities of an impending flood or storm surge hours in advance, so they can shut down equipment and move people to safety. Early warning is a cornerstone of ASEAN’s new Ha Long Declaration (2023) on anticipatory action, which Vietnam champions.

- Investing in Resilient Infrastructure: Hard infrastructure defenses are being built or reinforced to shield industrial and urban areas. This includes stronger dike and levee systems along major rivers and coasts, sea walls in vulnerable coastal zones, riverbank reinforcement, and better urban drainage. Such projects are already underway – for example, a major dyke system is being constructed along the Red River to protect industrial areas of Hanoi and surrounding provinces from floodwaters. In coastal industrial zones, mangrove reforestation and embankments are used as natural buffers. The government and World Bank’s “Resilient Shores” initiative has identified critical infrastructure upgrades to protect coastal economic hubs. These measures, while costly, are critical: engineering solutions like dikes and sea walls can significantly reduce the impact of typhoons and high tides on factories and ports. Likewise, elevating roads or building new reservoirs helps control flooding that would otherwise inundate industrial parks.

- Risk-Informed Industrial Development: Vietnam’s industrial and urban development strategies themselves are shifting to embrace resilience. New industrial parks must assess environmental and disaster risks during planning. There is a push to develop “smart” industrial zones with built-in flood control (e.g., retention ponds, pumping systems) and emergency power. The government is also promoting the concept of eco-industrial parks, some of which include climate adaptation features. By focusing on the most vulnerable locations and sectors – like low-lying Mekong Delta provinces – authorities aim to prioritize resilience investments where they matter most.

- Insurance and Financing Mechanisms: An emerging area of strategy is the use of financial tools to manage disaster risk. Vietnam is exploring disaster risk financing solutions, such as a national disaster fund and encouraging insurance uptake for businesses. Currently, less than 20% of companies in Vietnam feel confident they are prepared for major risks, and insurance penetration for disaster cover is low. Policies are being crafted to incentivize companies to purchase coverage (e.g. parametric insurance that pays out quickly after an event), and to establish contingency funds that can aid industrial recovery. Pre-arranged financing – one of the ASEAN anticipatory action pillars – ensures that when a disaster hits, funds are immediately available for relief and rebuilding.

- Whole-of-Society Engagement: Vietnam’s approach recognizes that resilience is a shared responsibility. The government has set up platforms like the Disaster Risk Reduction Partnership (DRRP) that involve not just ministries but also the private sector (including industry associations) and NGOs. This collaborative approach means industrial enterprises have a seat at the table in policy discussions and can share best practices or needs. Companies are encouraged to form mutual support networks – for example, factories within an industrial zone might pool resources for a shared fire brigade or joint evacuation drills.

By implementing these strategies, Vietnam has been shifting from reactive disaster response to proactive risk management. The industrial sector today is far better organized than a decade ago to handle disasters. Many factories have business continuity plans, backup generators, and safer storage for toxic materials. Building codes now require stronger structures and consider hazards like wind loading and seismic forces. And importantly, disaster risk reduction is being mainstreamed into Vietnam’s development plans – meaning every new highway, power plant, or industrial project is increasingly evaluated through a “resilience lens” before approval.

Technology and Innovation for Resilience

Technology plays a pivotal role in helping Vietnam’s industries anticipate and withstand natural disasters. Advances in monitoring, communications, and engineering are being leveraged to create smarter, more resilient industrial systems.

Early Warning Systems (EWS): Vietnam has dramatically improved its early warning capabilities for storms and floods. The national meteorological service now provides more accurate storm track forecasts days in advance, and a network of rain gauges and flood sensors feeds data to a centralized Disaster Management Information System. Many factories, especially those in flood-prone areas, are linked into these warning systems. They receive alerts that trigger internal response protocols (e.g. shutting off electrical equipment or moving raw materials to safe storage). For example, during a severe weather forecast, an electronics plant might delay shipments or secure its machinery based on timely warnings. Early warnings save lives and assets – a lesson proven in other disaster-prone regions and now being applied in Vietnam.

Digital Hazard Mapping: High-resolution satellite imagery and GIS mapping tools are identifying risk zones with greater precision. Industrial investors can now access digital maps that show the 100-year floodplain, earthquake fault lines, or areas of past landslides. This data is often built into the planning stage. Additionally, Vietnam’s cities are developing open-data portals where businesses can query local risk factors. For instance, a flood risk atlas allows an industrial warehouse developer to check if a proposed site has been underwater in past flood events.

Resilient Construction Techniques: Modern engineering innovations are being adopted to make factories and other facilities tougher. Structural retrofitting is one area – older factories built decades ago are being evaluated, and some are getting upgrades like roof reinforcements, braced frames, or base isolators (for seismic protection). New buildings often use wind-resistant design such as aerodynamic roofs, storm shutters, and stronger column connections to handle typhoon winds. In flood-prone zones, factories are now commonly built on elevated pads or stilts, and critical systems like electrical control rooms are placed on higher floors. These design tweaks, informed by engineering R&D, can dramatically reduce damage. Improved building codes and construction practices – such as stronger foundations, steel reinforcement, and quality materials – are vital for ensuring factories and commercial buildings can withstand earthquakes and storms.

Infrastructure Resilience Technologies: Beyond buildings, technologies are used to protect infrastructure networks that industries rely on. Smart grids and backup power solutions are being installed to reduce power outages. Some industrial parks have invested in on-site solar plus battery systems that can keep essential operations running if the main grid fails during a storm. In the transportation sector, sensors on bridges and roads monitor stress and flooding in real time; authorities can then close or reinforce critical routes before they collapse. Drainage pumping stations in cities are now automated and remotely controlled, activating when water levels rise to prevent factory districts from flooding. There are also pilot projects using IoT (Internet of Things) devices – such as river level sensors that send alerts to factories downstream, or vibration sensors on buildings that detect early signs of structural strain.

Climate-Adaptive Landscaping: A softer but innovative approach is using nature-based solutions to complement technology. Industrial zones are incorporating green features like bioswales, permeable pavements, and retention ponds to absorb rainwater and mitigate flooding. Along coastlines, planting mangroves and restoring wetlands near industrial ports has proven effective in breaking wave energy and reducing erosion during storms. These measures are often combined with engineering (hybrid solutions) for maximum effect. They not only protect assets but also provide co-benefits like improving the environment of industrial estates.

Simulation and Scenario Planning: Companies are using advanced software to simulate disaster scenarios and plan responses. For instance, larger corporations run earthquake simulation models on their factory designs to see how they would perform, allowing them to tweak structural elements virtually. Flood modeling software can predict how water would flow through an industrial park in various rainfall scenarios, guiding where to build flood walls or what ground level to maintain. Scenario analysis helps businesses “stress-test” their strategies against different futures. Vietnamese businesses are increasingly engaging in such forward-looking exercises, often with help from international consultants or NGOs, to ensure they are not caught off-guard by an extreme event.

Communication Tech for Crisis Management: When disasters hit, communication is key. Many industrial firms in Vietnam now use mass notification systems (via SMS, email, or mobile apps) to instantly alert all employees about emergencies and instructions. Some have adopted two-way communication apps that let workers mark themselves safe or request help. Drones are another tech tool coming into play – after a flood or earthquake, drones can quickly survey damage across a large factory complex, helping managers assess where help is needed before sending teams in. During severe flooding events, some companies have used drones to inspect factory roofs and facilities that were inaccessible by road.

In summary, technology and innovation are empowering Vietnam’s disaster resilience efforts. By combining high-tech solutions (like hazard modelling and early warnings) with practical engineering and nature-based approaches, the industrial sector is enhancing its ability to anticipate, absorb, and recover from shocks. Continued investment in these technologies – and ensuring they are accessible not just to big corporations but also to smaller local enterprises – will be crucial as climate risks grow. The trajectory is positive: Vietnam is actively embracing new ideas to safeguard its development gains.

Partnerships and International Cooperation

Vietnam is not building resilience in isolation. International cooperation and partnerships play a vital role in enhancing the country’s disaster preparedness, bringing in global expertise, funding, and collaborative frameworks.

The partnership with the International Finance Corporation (World Bank’s private sector arm) on the Building Resilience Index is a prime example. By piloting BRI in Vietnam, IFC has provided a cutting-edge tool plus training for local developers. The World Bank, through the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery, has also been supporting Vietnam for over a decade in mainstreaming resilience. This collaboration has yielded projects in transport resilience, urban flood control, and hydrometeorological system upgrades. For instance, World Bank financing helped build weather-proof roads and irrigation in rural areas, benefiting communities and industries (like agriculture and agro-processing) by reducing disaster disruptions. Vietnam’s close work with the World Bank has also informed its policies, contributing to disaster prevention laws and a comprehensive review of the hydrometeorology sector, which guided reforms in early warning practices.

The United Nations agencies and various non-governmental organizations are active in Vietnam’s disaster risk reduction. In January 2024, the UN Resident Coordinator in Vietnam convened a meeting highlighting the role of NGOs and the private sector in anticipatory action. Programs by UNDP have built storm-resistant housing for vulnerable communities (indirectly protecting the workforce that supplies industry) and are working with local authorities on climate adaptation plans for economic sectors. The Red Cross and other NGOs often partner with industrial zones for emergency response training and first aid education. These partnerships strengthen community resilience, which in turn benefits industrial resilience, since communities and factories often coexist in the same at-risk areas.

Regionally, Vietnam is a key player in ASEAN’s disaster management initiatives. In October 2023, as chair of the ASEAN Ministerial Meeting on Disaster Management in Ha Long, Vietnam helped adopt a Ministerial Statement to strengthen anticipatory action across ASEAN. The agreed approach focuses on risk information, strategic planning, and pre-arranged financing, all areas highly relevant to protecting industries. ASEAN cooperation allows Vietnam to share and receive best practices with neighbors, such as learning from Indonesia’s tsunami warning systems or the Philippines’ typhoon evacuation schemes. Joint simulations and drills are conducted under ASEAN frameworks, some of which include cross-border supply chain scenarios. Additionally, Vietnam is part of the ASEAN Disaster Risk Financing and Insurance program, exploring pooled insurance solutions for catastrophes.

In 2025, Vietnam took a significant step by announcing it will join the global Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure, an initiative led by India. By becoming the 40th member of CDRI, Vietnam aligns with an international effort to promote resilient infrastructure development. This opens avenues for technical assistance and knowledge exchange on making roads, bridges, industrial parks, and energy systems more robust against natural hazards. CDRI membership can especially benefit Vietnam’s industrial sector through shared research on topics like resilient industrial park design or risk assessment methodologies. It also signals Vietnam’s commitment on the world stage to building infrastructure that can endure climate stresses.

Various countries have supported Vietnam’s resilience journey. Japan has funded projects to improve dam safety and earthquake monitoring. The USA has worked on flood forecasting and urban resilience initiatives. European nations have supported climate adaptation in the Mekong Delta, crucial for agriculture and related industries. The Green Climate Fund is financing a project to strengthen coastal community resilience with safer homes and mangrove planting. Such projects often involve local stakeholders and industries. For instance, a coastal seafood processing company might collaborate on mangrove restoration that protects its facilities from storm surges.

International companies operating in Vietnam are also part of the resilience push. Many multinationals in electronics or textiles require their local suppliers to have risk mitigation plans. Groups like BSR (Business for Social Responsibility) are working with companies to address climate risks in supply chains. Some foreign-invested industrial zones incorporate world-class safety standards and can serve as models for local developers. Insurance firms from abroad are advising on risk transfer solutions for Vietnamese infrastructure. All these interactions help transfer knowledge and raise the bar for the entire industrial sector.

Vietnam’s openness to international cooperation has clearly paid dividends. Over the past decade, these partnerships have helped Vietnam protect millions of people and billions in assets through better planning and preparedness. For example, community-based projects supported by donors have benefited over 3 million Vietnamese and employed tens of thousands in resilience works, such as maintaining irrigation canals. As disasters do not respect borders, staying connected with global initiatives ensures Vietnam’s industrial sector stays ahead of emerging risks, whether it’s learning about the latest seismic design techniques or accessing climate funds to build resilience.

Conclusion

Vietnam’s industrial sector has come a long way in recognizing and addressing disaster risks. The convergence of climate change impacts and natural geological hazards poses a serious challenge, but one that Vietnam is meeting with determination and innovation. Recent disasters – from ferocious typhoons to faraway earthquakes that rattled its cities – have only reinforced the importance of building resilience. In response, Vietnam is fortifying its factories, updating its policies, and harnessing new tools like the Building Resilience Index to ensure that growth is not only fast but also sustainable in the face of shocks.

The strategies unfolding in Vietnam offer valuable lessons. A multi-pronged approach is key: robust infrastructure, effective early warnings, strong governance, community engagement, and international support all reinforce each other. By investing in resilience, Vietnam is effectively buying “insurance” for its development gains – reducing future disaster losses and speeding up recovery. This is particularly crucial for industry, where a single disaster can disrupt supply chains and livelihoods nationwide.

There is still work to be done. Climate science suggests that extreme weather will intensify, and rapid urbanization means more assets are exposed. Continuous improvement of building standards, enforcement of regulations, and incorporation of the latest technologies will be needed. Small and medium enterprises, which make up a large part of Vietnam’s industry, will need more support and awareness to adopt resilience measures (since they are often the most vulnerable). Financing mechanisms must be expanded to help retrofit existing structures and build new resilient facilities.

Overall, Vietnam’s trajectory is one of learning and adapting. From the policy halls in Hanoi to the factory floors of Binh Duong, there is a growing culture of safety and foresight. The industrial sector, in partnership with the government and global community, is striving to ensure that the next big storm or tremor won’t derail the nation’s progress. With continued commitment, Vietnam is poised to become a regional leader in industrial resilience – proving that economic development and disaster preparedness can and must go hand in hand.

Sources

Asian Development Bank. (2023). Strengthening Climate and Disaster Resilience in Southeast Asia. Retrieved from https://www.adb.org

World Bank. (2022). Vietnam: Climate Resilient Industrial Development. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org

UNDRR. (2023). Disaster Risk Reduction in Vietnam. Retrieved from https://www.undrr.org

Vietnam News. (2024, March 10). Recent Earthquake in Northern Vietnam Highlights the Need for Resilient Infrastructure. Retrieved from https://vietnamnews.vn

Thanh Niên. (2024, February 25). Bão lũ miền Trung và tác động đến khu công nghiệp. Retrieved from https://thanhnien.vn

Vietnam Ministry of Construction. (2023). National Resilience Index for Industrial Infrastructure. Retrieved from https://moc.gov.vn

ISO. (2023). ISO 14090: Adaptation to Climate Change — Principles, Requirements, and Guidelines. Retrieved from https://www.iso.org